Jumping Off the Infernal Wheel:

Buddhism and Teenage Suicide

by Paki S. Wright

In writing The All Souls' Waiting Room: A Black Comedy about Karma and

Killing Yourself, a novel that begins with the young protagonist's adolescent depression and attempted teenage suicide,

I had no idea I was tapping into what is called a "silent epidemic." In writing The All Souls' Waiting Room: A Black Comedy about Karma and

Killing Yourself, a novel that begins with the young protagonist's adolescent depression and attempted teenage suicide,

I had no idea I was tapping into what is called a "silent epidemic." Disturbingly,

according to the World Health Organization, worldwide suicide statistics indicate an upward trend. China, for instance, has

the highest incidence of suicides among young people in the world, with very limited access to professional help. (1) Since

so many people are suffering from suicidal ideation and suicidal tendencies -- from unhappy adolescents, lesbian/gay/bisexual

and trans-gender persons, victims of teenage and/or Facebook bullying, increasing numbers of veteran suicides, debt- and drought-burdened

East Indian farmers, to people depressed over the loss of work, housing, financial security -- I wanted to examine the phenomena

of suicide and depression from the personal perspective of a Western Buddhist writer, which is of course by no means the last

word on the subject.

When I was a teenager, unbeknownst to me, I had all the known risk factors for

suicide: my parents were divorced, I had experienced early childhood abuse, lived with an alcoholic single parent, and had

literally no family network. Moreover, I grew up in New York City during the Cold War of the 1950's, not exactly a time of

peace and light. On top of it all, my mother belonged to a group of Reichian free-thinkers who were persecuted for their nonconformist

beliefs during the witch-hunt years of the McCarthy era.

Spiritual Suffering I was also, however -- and I have a theory that this holds true for many suicidal people, particularly adolescents

thinking about suicide -- highly intelligent, creative and idealistic. In my case, it was a combination

of stressors that put me over the edge: feelings of personal failure, rejection, and depression.Luckily, I didn't succeed

in killing myself, even after two attempts. Yet there are thousands of deaths from teen suicides yearly in the U. S.; different

sources give the totals between 4,000 and 10,000. Whatever the number, it is many too many.

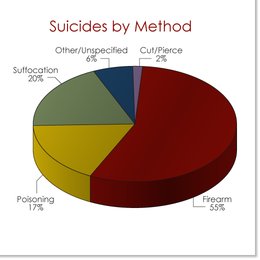

Some of the reasons given for the increased youth suicide rates are family splintering, more drug and alcohol

abuse, access to guns, and increased competition at earlier ages. These are some of the specifics, but I would add a few more:

environmental degradation, the pressures of overpopulation, and a deepening sense of despair about the future. Some of the reasons given for the increased youth suicide rates are family splintering, more drug and alcohol

abuse, access to guns, and increased competition at earlier ages. These are some of the specifics, but I would add a few more:

environmental degradation, the pressures of overpopulation, and a deepening sense of despair about the future.

And

yet suicide is never a viable option for opting out of life's inevitable pain and suffering. In Buddhist terms, it just gets

you out of the frying pan and into the fire.

Young people who even think about, much less attempt suicide

are the canaries in the coal mine of our nihilistic mass culture. A healthy society would not have so many young people --

at younger and younger ages -- trying to kill themselves. Suicidal tendencies in children are saying we're on the wrong

track. We can deny or repress the message, but that won't change the situation. We need a new perspective, new answers.

Most Westerners know that suicide is considered a mortal sin in Judeo-Christian terms. Buddhism has no concept

of sin, but it does have one of negative karma -- something that we have control over creating, or not. It's important

to understand that Buddhism is both "pro-life and against attempts to legislate individual morality." This means

we don't make decisions for others, or judge them for what they do. However, there are certain things a Buddhist will take

as given, since the Buddha's followers generally believe in reincarnation and karma

(but not at all necessarily as a human).

Karma, simply put, means "action." Positive results

follow from positive actions, negative results follow from negative. This is virtually the same as the Biblical injunction,

"As ye sow, so shall ye reap."

Rebirth means that our consciousness continues after death,

taking form in other lives. Thus, "while death means an end to the physical body, it does not mean an end to the mental

continuum." This is both good and bad news. (One of my esteemed Tibetan Buddhist meditation teachers, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche,

said more than once, "Unfortunately, there is no death.")

The potentially good

news is we don't die in the total oblivion, lights-out sense. The potentially bad news is that "whatever habits and traits

one has cultivated, both positive and negative, will 'spill over' into another life." We don't necessarily gain rebirth

as a human being after we die; having two human incarnations in a row is said to be very rare. The human is only one of six

realms (the other five are hell realms, hungry ghost, animal, jealous god, and god realms). Our human realm, then, even with

all its faults and foibles, is unquestionably the most favorable for spiritual development because it alone has the right

mixture of spiritual suffering (for motivation) and freedom to act on this inspiration. This is why the term "precious

human rebirth" is used. The other realms don't have the right "mix."

But --another proviso

-- not even all human rebirths have the necessary ingredients to be considered "precious." One needs incredible

amounts of positive karma to be able to follow the path to liberation. If you have the chance and you blow it, well . . .

it's analogous to landing on a jewel-covered island and leaving empty-handed.

Everybody dies. Yet how we die can determine a lot about our future lives. The ideal Buddhist death is "to

die without anxiety regarding those one leaves behind and in a conscious state which is calm and uplifted" -- rarely

the case with suicides. One must learn one's lessons and live out the karma of this particular life; a self-enforced

death cuts short the process. A natural death gives us the rare opportunity to reflect on the nature of attachment and the

suffering it inevitably brings. Everybody dies. Yet how we die can determine a lot about our future lives. The ideal Buddhist death is "to

die without anxiety regarding those one leaves behind and in a conscious state which is calm and uplifted" -- rarely

the case with suicides. One must learn one's lessons and live out the karma of this particular life; a self-enforced

death cuts short the process. A natural death gives us the rare opportunity to reflect on the nature of attachment and the

suffering it inevitably brings.

From a Buddhist perspective, the meaning of life is to become enlightened, so that

one can then be of ultimate benefit to all sentient beings. This is not possible without a body as a vehicle, therefore the

body is precious, because it will bring one to the highest happiness: freedom from suffering.

While it was

clear to me as an anguished teenager that life was full of suffering in one form or another, I thought it was my fault, that

I had somehow brought it on by my own behavior. Since I didn't see how I could change anything, I thought suicide was the

only way out. However, in Ven. Thrangu Rinpoche's words, "Once one is aware of how suffering takes place, then one can

begin to remove the causes of suffering."

Idealistic young people need high ideals, ways of channeling

their positive energies into constructive outlets -- instead of shopping at the local factory outlet. They need to do things

that make contributions to society, that elevate their self-esteem and give them tangible emotional satisfaction. The one

thing we can always do, no matter what the situation, is help each other. No matter what else prevails, helping others redeems

our lives. This is the main tenet of Buddhism, for only by helping others do we truly help ourselves -- out of our own selfishness,

egoism, and indifference. Buddhism and Teenage SuicideOften, seemingly simple things like family support, decent grades, getting

enough sleep -- and exercise --- can have powerfully positive results in attitudes about living. Many teenagers, for instance,

don't value the importance of eating well. I know I didn't, but my habit of bingeing and then fasting did drastic things to

my brain chemistry and subsequent moods. Ironically, if I'd thought of my body as a vehicle I might have treated myself better.

Everybody knows cars don't run well on bad gas -- or at all if the tank is empty. Especially important is substance

abuse counseling, since almost 90% of all suicides and suicide attempts are associated with some form of misuse of drugs or

alcohol. I know that in my case, I could

really have used some meditation training. I needed some way of seeing the temporary, impermanent nature of thought, some

way of freeing myself from negative, self-destructive ideas. It's not very difficult to learn how to tell harmful thoughts

from positive ones. As Tibetan Buddhist nun Ani Tenzin Palmo said, "The main benefit of meditation is being able to choose

which thoughts to follow." Plainly, too many young people follow their darkest, most desperate ones - suicidal tendencies.

From a Buddhist perspective, we are all on our way to becoming

buddhas (admittedly some sooner than others, but that's another story). If all beings knew how

precious their lives are, how precious they are, how precious is this sometimes excruciating,

sometimes exquisite opportunity for growth and liberation called life, would teenage suicide even

exist? (1)

New Yorker, January 10, 2011, "Meet Dr. Freud" |

|

|